We often come across historic reports of drowning during our research. This case attracted our interest as it was relatively local, and the inquest was reported in some detail. The following is based on reports in the Western Gazette.

There is more detail about some of the people and places mentioned at the bottom of the page.

On the morning of Thursday 12th December 1895, the body of a young woman was found in the River Avon in Ringwood, Hampshire. She was named locally as Elizabeth Lucas, a ‘tramp’, aged about 23.

On the following evening the coroner, Mr F A Johns, held an enquiry at the New Inn. Mr J C Baines was chosen as the foreman of the jury.

The first witness called was Herbert Moore Sutton, master of Ringwood Workhouse, who identified the body as that of Elizabeth Lucas, a wayfarer. She’d been to the workhouse as a casual the previous Monday night and left late the next morning. She told him she’d come a day too early for the winter fair by mistake and was going to Fordingbridge Tuesday afternoon, to return to Ringwood on Wednesday.

John Tidy, landlord of the White Lion, said the deceased was in his inn on Wednesday evening between seven and half-past. He believed she was with a young man called Henry Blake. He called for some beer, but as he said he had no money, he wasn’t served, and they went out together.

After being cautioned by the coroner, Harry Blake, appeared next. He said he lived at Kingston, that he didn’t know the deceased, was not with her on Wednesday evening and wasn’t in the White Lion.

The coroner recalled John Tidy who insisted that it was Blake he’d seen and said two others could confirm it.

When Blake was asked again if he’d been there, he replied “Not that I know of, I was not there”. He did admit that he’d lost his money and he’d had a lot of beer. He also remembered being with a woman he didn’t know at the Royal Oak. She said she was married and from Fordingbridge. She asked him for some beer at the Royal Oak and he’d bought her a glass.

Bowering, a waiter at the White Lion, said that Blake had been there. He was drunk and the woman sober. She was wearing a dark red shawl like the one produced at the inquest.

When Blake was asked if he anything more to say he replied “No, sir; it’s the truth what I have said. She went off as soon as I went out of Mr. Tidy’s”. When the Coroner asked again if he had been in the White Lion, he said he couldn’t remember, but that’s what everyone said.

Henry Randall, a labourer living in Ringwood, found the body the following morning. He’d heard that a woman had been drowned and got into boat with Robert Tuck to search for the body in the millstream. They found her between some piles.

Florence Gear, barmaid at the Royal Oak, reported seeing Blake in the bar with a woman at about seven o’clock; he was not drunk. Just afterwards she saw Blake and a woman and another man in Star Lane. The man was hitting Blake and the woman told him not to. She could not identify the man or the woman. The woman did not have a red wrap on. The other man was not ‘Long Charley’ (Charles Saunders).

When called back, Blake said he left the Royal Oak by the front door. He didn’t go into the lane, didn’t see a man with a woman and nobody had hit him.

The next witness was Charles Saunders, who was also cautioned. In reply to questions, he said he was a labourer from Lower Kingston and was in Ringwood on Fair Day until 11pm. He didn’t remember seeing the deceased. He was in the Royal Oak until around 7.20 but didn’t see Blake or any woman there. He was then in The Star till eight.

Dr. H. C. Dyer said he’d conducted a post-mortem examination on the Thursday. The victim’s face had a very bloated appearance, and he thought she was a drunkard. He found no marks of violence. The tongue was protruding, and the skin indicated immersion in water. Her stomach was full of water and beer. She must recently have been drinking beer. The lungs were full of water, indicating she was alive she entered the water. The cause of death was drowning, and he thought she must have been very exhausted when she fell into the water.

William Hiscock, landlord of the Star Inn, said Saunders was in his pub late on Wednesday, but he could not say at what hour.

Harry Thomas, a carter at the mill (employed by Mr. Atkins), said that on Wednesday evening, between 7.30 and 7.45, he was coming down Mill-lane, and was about 20 yards from the ‘Black House’ when he stood still for a while. He heard man step into the road about 25 yards away, and call “Come on” to somebody three times, before walking towards the Mill. Mr Thomas then heard a splash in the water and walked towards the Black House. Just as he got ‘over-right’ where he saw the man come out, he heard a loud scream and ‘guggling’ as if a woman was in the water.

He went to the riverside but couldn’t see anything. On returning to the road, he heard four screams of “murder” from the person in the water. He ran after the man he’d seen and put his hand on his shoulder, saying “For God’s sake come back, the woman at the Black House is drowning.” The man replied, “I can’t help it, can I?”. Harry Thomas said “Let’s go back and try to get her out” but the man walked away towards Stannard’s-lane.

Harry ran into the town for help, and several men came back with him. He sent someone for the police and went to fetch a lantern. When questioned by the coroner, he said he was sure the man was Charles Saunders and that he appeared to be sober. He couldn’t say how dark the night was, but the incident was almost in the gaslight. And, when pressed, that he was “pretty well or quite sure” it was Charles Saunders. When asked if he called him by name, Mr Thomas said he called “Charley, for God’s sake come back”. He said Saunders was wearing a brown topcoat and a soft black hat.

Saunders was re-called and said he wore an overcoat and a hard hat—not a soft one like the one he was holding at the inquest. Superintendent Hadden told the coroner he saw Saunders with a soft felt hat on Wednesday night.

Saunders said he hadn’t been in Mill Lane with a woman. He knew Thomas, but not by name, and didn’t see him at all that night.

In summing up, the coroner said he thought they could not rely upon a word that Blake had said, but it wasn’t important, because evidently it wasn’t him who was with the woman in Mill-lane.

If they believed what Harry Thomas said, Saunders was with the deceased near the Black House; for what object they could only surmise. But he couldn’t have pushed the woman into the water, because the splash was heard after the man called out ” Come on.”

Why he (Saunders) chose to tell so many lies they didn’t know. Perhaps he didn’t want the jury to know why he was there; but what he said was evidently untrue. There was no doubt, from what Thomas had said, that the man was there. Judging from the evidence, the coroner did not think it was a case either of suicide or murder, and it seemed him that the woman must have slipped into the water accidentally.

The jury at once returned a verdict of accidental death by drowning. The foreman, Mr. Baines, said that, in their opinion, Saunders took the woman there and left her there. And then she either turned the wrong way or slipped into the water. They thought Saunders ought to be severely censured for not going back to give assistance. It was also their opinion that the attention of the Earl of Normanton (of Somerley, the main local landowner) should be called to the want of a fence by the side of the road.

Saunders was then called in and censured by the coroner, who told him that the jury thought that, by not rendering assistance, he was morally guilty of contributing to the woman’s death. Saunders again denied being with the woman.

The jury also wished Mr Thomas to be commended for his actions. The coroner did this and then closed the inquest.

* * *

So, who was the unfortunate Elizabeth Lucas? We have a theory, but it would take a lot more work (or luck!) to prove it. Another story for another day perhaps……

The coroner Francis Arthur Johns (1855-1940) was a solicitor from Ringwood, where his father had also been a solicitor and coroner. F A Johns was coroner of the Ringwood Hundred for 57 years. And of the Cranborne Hundred for 52 years. He conducted nearly 600 inquests, many of them in public houses and rural homes. In 1881 he became registrar of the county court. As a young man he captained Ringwood cricket and football teams. He served as an officer in 2nd (Volunteer) Battalion, Hampshire Regiment for 12 years. For 5 years he was chief officer of Ringwood Fire Brigade. He was a freemason and became Master of Ringwood Unity Lodge.

Ringwood Workhouse was established in a row of cottages on the road to Verwood at Ashley in 1725 and could accommodate up to 160 inmates. It’s now been converted back to houses.

‘Casual’ inmates at a workhouse were tramps, or the like, who weren’t from the local parishes (whose rates paid for the workhouse) and were given very basic overnight accommodation in return for them doing several hours of work the following morning. Once they’d finished their work they were not encouraged to stay and would usually move on to the next nearest workhouse.

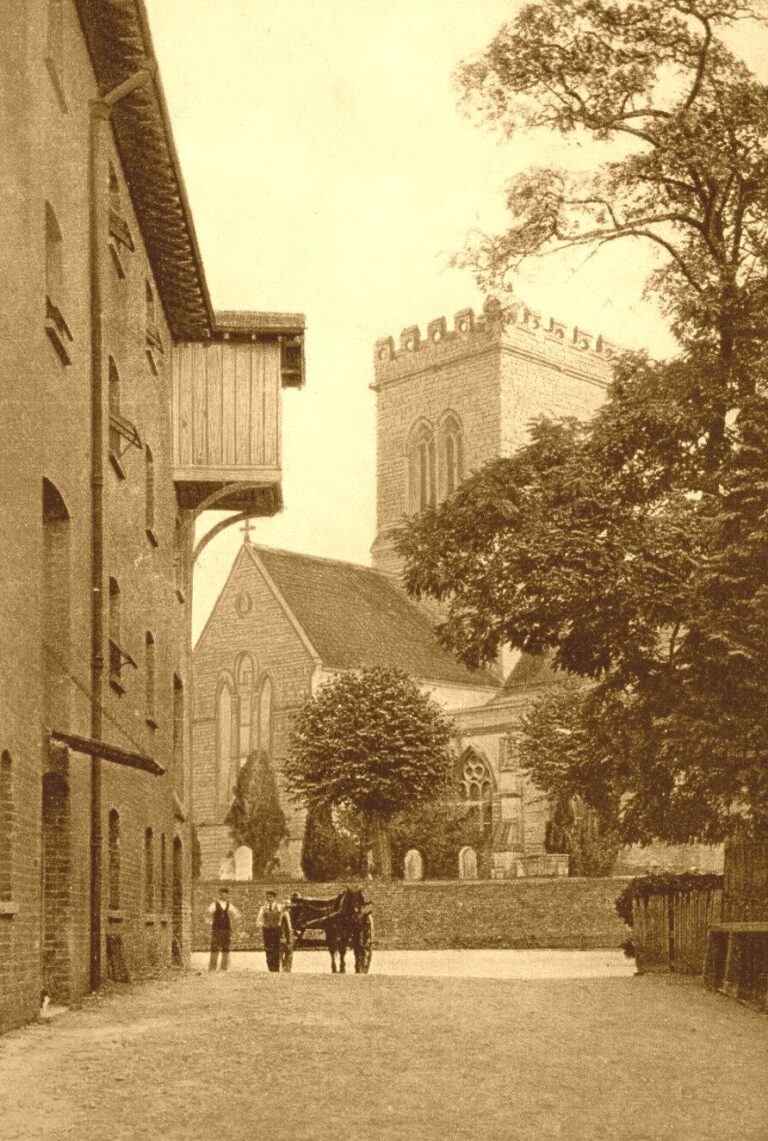

The New Inn was on the corner of West Street and Market Square.

The Royal Oak was in the Market Place, on the opposite side of Star Lane to the Star Inn.

The White Lion was on the corner of Dewey Lane and Market Square.

Kingston is on the Christchurch Road, about a mile south of Ringwood.

Star Lane runs from the High Street, past the Star Inn, to (what’s now) the Furlong Shopping Centre.

The Star Inn is still in the Market Place, next to Star Lane.

Mill Lane ran past the mill, over the millstream, to the marketplace. The mill was fed directly by the River Avon, with a short millstream beyond and sluices to feed excess water to the adjacent water meadows.

Stannards Lane ran east from the Mill. The access to Waitrose car park ‘Stallards Lane’ runs just north of the original lane.